Project 1A: Increasing iPSC Yield

Table of Contents

Introduction #

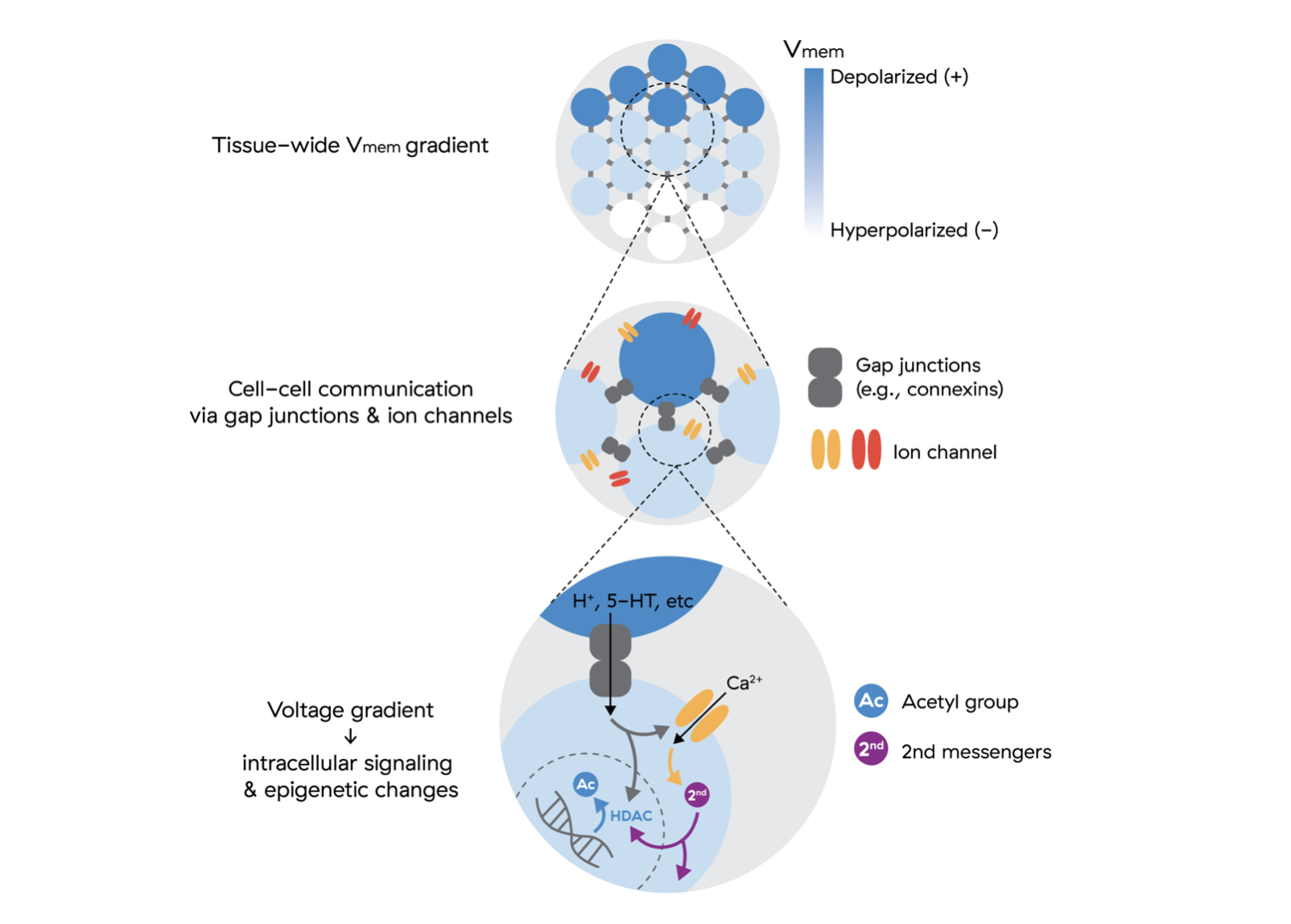

The purpose of Project 1A is to utilize a bioelectric strategy to increase the yield of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) during cell reprogramming. We will integrate electrophysiological data we record during the reprogramming process to inform said strategies, creating a feedback loop between computational modeling and experimentation. Our benchmark goal is 10%. Our core hypothesis is that by modulating the signals cells use to coordinate towards shared goals as opposed to micromanaging the underlying single cell state, we can more effectively control cell fate during reprogramming.

If you have questions about anything you read here, or are interested in joining our internal efforts to tackle these objectives, send us a note to info@aion.bio.

What we know #

- Cells can be reprogrammed without transcription factors. 1 2

- We can direct cell fate by modulating membrane potential. 3 4 5 6

- We can reversibly block mitosis by altering membrane potential. 7

- Small molecules can be used with transcription factors to increase the yield of iPSCs and the speed of the reprogramming process. 8 9

- Endogenous voltage potentials play an important role in cell communication and coordination. 10 11 12

- The majority of reprogramming methods are less than 1% effective.13

What we think #

A bioelectric approach to reprogramming will lead to an order of magnitude increase in the yield of iPSCs.

How we will find out #

- Benchmark existing reprogramming techniques for consistency of results measured against iPSC yield.

- Develop a robust voltage reporting technique to use on non-excitable cells.15

- Utilize voltage reporting technique from (2) on cell reprogramming method from (1).

- Use data from (3) to create synergistic feedback loop between computational models16 and experimental trials in chemical reprogramming to increase iPSC yield.

Guan, J., Wang, G., Wang, J. et al. Chemical reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotent stem cells. Nature 605, 325–331 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04593-5 ↩︎

Yang JH, Petty CA, Dixon-McDougall T, Lopez MV, Tyshkovskiy A, Maybury-Lewis S, Tian X, Ibrahim N, Chen Z, Griffin PT, Arnold M, Li J, Martinez OA, Behn A, Rogers-Hammond R, Angeli S, Gladyshev VN, Sinclair DA. Chemically induced reprogramming to reverse cellular aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2023 Jul 12;15(13):5966-5989. doi: 10.18632/aging.204896. Epub 2023 Jul 12. PMID: 37437248; PMCID: PMC10373966. ↩︎

Sempou, E., Kostiuk, V., Zhu, J. et al. Membrane potential drives the exit from pluripotency and cell fate commitment via calcium and mTOR. Nat Commun 13, 6681 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34363-w ↩︎

Sundelacruz S, Moody AT, Levin M, Kaplan DL. Membrane Potential Depolarization Alters Calcium Flux and Phosphate Signaling During Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Bioelectricity. 2019 Mar 1;1(1):56-66. doi: 10.1089/bioe.2018.0005. Epub 2019 Mar 21. PMID: 32292891; PMCID: PMC6524654. ↩︎

Thrivikraman G, Boda SK, Basu B. Unraveling the mechanistic effects of electric field stimulation towards directing stem cell fate and function: A tissue engineering perspective. Biomaterials. 2018 Jan;150:60-86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Oct 3. PMID: 29032331. ↩︎

Sundelacruz S, Levin M, Kaplan DL. Role of membrane potential in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2009 Sep;5(3):231-46. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9080-2. Epub 2009 Jun 27. PMID: 19562527; PMCID: PMC10467564. ↩︎

Cone CD Jr, Tongier M Jr. Control of somatic cell mitosis by simulated changes in the transmembrane potential level. Oncology. 1971;25(2):168-82. doi: 10.1159/000224567. PMID: 5148061. ↩︎

Zhang Y, Li W, Laurent T, Ding S. Small molecules, big roles – the chemical manipulation of stem cell fate and somatic cell reprogramming. J Cell Sci. 2012 Dec 1;125(Pt 23):5609-20. doi: 10.1242/jcs.096032. PMID: 23420199; PMCID: PMC4067267. ↩︎

Bar-Nur O, Brumbaugh J, Verheul C, Apostolou E, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Walsh RM, Ramaswamy S, Hochedlinger K. Small molecules facilitate rapid and synchronous iPSC generation. Nat Methods. 2014 Nov;11(11):1170-6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3142. Epub 2014 Sep 24. PMID: 25262205; PMCID: PMC4326224. ↩︎

Matthew P. Harris; Bioelectric signaling as a unique regulator of development and regeneration. Development 15 May 2021; 148 (10): dev180794. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.180794 ↩︎

Levin M. Molecular bioelectricity: how endogenous voltage potentials control cell behavior and instruct pattern regulation in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2014 Dec 1;25(24):3835-50. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-12-0708. PMID: 25425556; PMCID: PMC4244194. ↩︎

George LF, Bates EA. Mechanisms Underlying Influence of Bioelectricity in Development. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Feb 14;10:772230. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.772230. PMID: 35237593; PMCID: PMC8883286. ↩︎

Al Abbar A, Ngai SC, Nograles N, Alhaji SY, Abdullah S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Reprogramming Platforms and Applications in Cell Replacement Therapy. Biores Open Access. 2020 Apr 28;9(1):121-136. doi: 10.1089/biores.2019.0046. PMID: 32368414; PMCID: PMC7194323. ↩︎

Anderson, Benjamin. “Bioelectricity: A top-down control model to promote more effective aging interventions.” Bioelectricity 6.1 (2024): 2-12. ↩︎

For more on this, see Project 1B. ↩︎